Space mining is moving from the realm of science fiction into serious development. Private companies and governments are exploring technologies to extract resources such as water, metals, and minerals from the Moon, asteroids, and beyond. But along with rockets and robots, an unlikely factor could make or break this industry’s future: intellectual property law.

How do patents and other IP rights apply to new methods and technologies used in space mining? This post will explore the challenges of patenting space mining tech under current U.S. and international legal frameworks, the legal grey areas of applying terrestrial IP law to outer space, and what it all means for innovation and investment in the space mining sector.

A New Legal Frontier: How Intellectual Property Law Applies to Space Mining Patents

Patents grant inventors exclusive rights to their inventions, but these rights are traditionally territorial, valid only within the borders of the issuing country. Outer space, however, is not any country’s territory. The foundational 1967 Outer Space Treaty declares that “outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty”.

In simpler terms, no nation can claim ownership over the Moon, an asteroid, or any patch of space. This creates a unique tension: patents rely on national jurisdiction, yet space has no sovereign jurisdiction. So, how can a patent be enforced “out there” in the legal void? Despite this challenge, nothing in international law outright forbids patenting a space mining invention.

The Outer Space Treaty’s ban on appropriation was intended to prevent territorial claims (e.g., planting a flag to claim a planet), not to prevent using or owning its resources. In fact, recent developments have clarified that extracting resources is permissible. The 2020 Artemis Accords, a multilateral agreement on principles for space exploration, explicitly state that “the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation.”

This means companies can legally extract and own resources, such as lunar water or asteroid minerals, without violating international law. By extension, it’s generally accepted that one can patent the technology for extraction, as long as the patent isn’t claiming ownership of celestial bodies themselves (you can patent a mining technique, but you can’t patent the Moon!).

Current Legal Frameworks: U.S. and International Laws

While international treaties set broad principles, the nitty-gritty of intellectual property in space is being hashed out in national laws. The United States, for example, has been proactive. In 2015, the U.S. passed legislation (the SPACE Act of 2015) recognizing private rights to resources mined from space. Uniquely, the U.S. also updated its patent law to address inventions in space.

35 U.S.C. § 105 provides that any invention “made, used or sold in outer space on a space object or component thereof under the jurisdiction or control of the United States” is considered to be made, used, or sold on U.S. territory. In plain English, if your patented device or method is used on a spacecraft that’s registered in the U.S. (for example, on a NASA or American commercial lunar lander), it’s as if the use occurred on U.S. soil, and your U.S. patent could be enforced. This was a deliberate fix to ensure patent coverage doesn’t evaporate once a rocket leaves Florida.

Other spacefaring nations are starting to follow suit in clarifying resource and IP rights. Luxembourg, a surprising early mover, passed a law in 2017 giving companies the right to own space resources they extract. Japan and the United Arab Emirates have also enacted laws permitting private ownership of mined space resources. These laws are primarily about property rights to minerals, but they create a friendlier environment for patenting space mining tech by assuring companies that their activities are lawful.

So far, the U.S. is the only country with a specific provision tying patent jurisdiction to space activities, but others may introduce similar measures as the sector grows. It’s worth noting that when nations collaborate in space, they often predetermine whose laws apply. For instance, on the International Space Station (ISS), each partner country retains jurisdiction over its own modules and personnel.

If an invention is made on the U.S.-owned segment of the ISS, U.S. patent law treats it as made in the U.S., and similarly for other countries’ modules. This segmented approach shows how countries can extend their IP laws to space in a cooperative framework. However, beyond specific arrangements like the ISS or national spacecraft, a comprehensive international system for space IP is still lacking.

Terrestrial Patents, Extraterrestrial Problems: Legal Grey Areas

The collision of terrestrial IP law with the extraterrestrial environment gives rise to several legal grey areas. One big question is jurisdiction.

Jurisdiction

Let’s say a company from Country A uses a patented mining method on an asteroid while operating a spacecraft registered in Country B. Whose law is at play? Normally, a patent is infringed only if the invention is used within the territory of the country that granted the patent.

If the activity happens entirely in space, outside any national territory, or on a spacecraft of another country, it might fall outside the reach of your patent. Companies, therefore, file for patents in multiple jurisdictions (U.S., Europe, China, etc.) to cover as many potential arenas as possible. They may also try to ensure the patent claims cover any Earth-based portions of the invention (like control systems or launch hardware) to strengthen enforceability.

Enforcement

Another grey area is enforcement. Let’s say you do detect a competitor using your patented asteroid drill on a distant asteroid. How do you enforce your rights? Who do you sue, and where? In practice, you would likely need to sue in the country where that competitor is based or where their spacecraft is registered, assuming you have a patent there. If the competitor is from a country with no comparable patent or isn’t keen on enforcement, you’re out of luck.

There is no “World Space Court” for patent disputes, and international law hasn’t yet established clear mechanisms for this scenario. Policymakers have been focused on clarifying ownership of resources, but intellectual property enforcement in space has not yet garnered the same attention, and there’s no robust, harmonized approach in place.

Infringment

A related challenge is simply detecting infringement. Space is big, and private operations may be hidden from public view. Monitoring what equipment or processes a competitor is using millions of kilometers away is no small task. Unlike on Earth, you can’t easily inspect a rival’s mining outpost or robot on an asteroid (at least not without their cooperation). This raises practical problems: a patent is only as good as your ability to know it’s being violated and bring a case.

Some companies worry about a “wild west” scenario where patents exist on paper but are routinely violated in remote locations with little oversight. There are also philosophical grey areas. Space is often called the “province of all [hu]mankind,” meant to benefit everyone. Some ask whether allowing exclusive patents on critical space mining methods might conflict with the spirit of space law that promotes freedom of exploration for all.

For now, the prevailing view is that patents on tools and techniques do not constitute appropriation of space (you’re not claiming the asteroid itself, just your inventive way of mining it). In fact, patent systems can encourage inventors to publish their innovations (via patent disclosures), which adds to the collective knowledge, aligning, in theory, with the idea that space activities should benefit humanity.

Still, if one company patented a “must-have” technology (say, a method to extract water from Martian ice) and refused to license it, it could create tension with international ideals. These are untested waters – or perhaps, untested vacuum – that legal scholars continue to debate.

Innovation vs. Uncertainty: Implications for Investment

Uncertainty in IP law can have real impacts on innovation and investment in the space mining sector. Developing technology to prospect and mine asteroids or the Moon is extremely costly and risky. Companies and their investors typically want some assurance that if they strike proverbial “gold” (or water, platinum, etc.), they can reap the rewards of their innovation without a competitor simply copying their tech.

Clear patent rights and enforcement mechanisms are seen as important safeguards for these high-tech, capital-intensive ventures. If a startup knows it can patent its revolutionary drilling system and prevent others from using it (at least for a limited time), it’s easier to attract funding for further R&D. On the flip side, if the legal environment makes it doubtful you could stop an overseas rival from cloning your asteroid-miner, you might be less inclined to invest in developing it in the first place.

Paradoxically, too much uncertainty could push companies toward trade secrets instead of patents, keeping their technology details secret so competitors never find out how it works. While that protects the invention in theory, it also means less knowledge sharing across the industry. Patents, by contrast, require disclosure of the invention in exchange for protection. Striking the right balance is key.

We want companies to innovate and share their breakthroughs (through patents or publications), but also feel secure that they’ll profit from their inventions. The current grey areas in space IP law are gradually being addressed precisely because they have implications for commercial confidence. Lawmakers in spacefaring nations are aware that unclear IP rights could become a barrier to the growth of the off-world economy.

We may see more bilateral or multilateral agreements ensuring that, say, each country will respect the space-related patents issued by the others, or perhaps new treaties under the auspices of the U.N. or WIPO to handle IP in outer space.

Pioneering Examples: Patents and Missions in Space Mining

Even with legal uncertainties, space mining pioneers are already staking their claims – not on celestial territory, but on intellectual property. Several companies have filed patents for technologies they hope will one day unlock cosmic resources.

(Ex) Planetary Resources

For example, the now-defunct Planetary Resources (an asteroid mining startup that was backed by prominent Silicon Valley investors) obtained patents on techniques for prospecting and mining asteroids. One of its patents describes a method of using a space telescope on a spacecraft to identify and catalog asteroids for mining potential.

Planetary Resources’ early patent portfolio reflected the high-tech approaches envisioned for off-world mining, from surveying asteroids to extracting water for fuel. (In an interesting twist, after the company was acquired in 2018, much of its intellectual property was later released into the public domain, illustrating how quickly the landscape can shift in this nascent industry.)

TransAstra

Another innovator, Trans Astronautica Corporation (TransAstra), has been actively developing and patenting its space mining architecture. TransAstra’s founder, Dr. Joel Sercel, is known as the inventor of an “Optical Mining” technique (using concentrated sunlight to break down asteroid material) and reportedly had over a dozen patents pending related to space resources and in-space transportation.

TransAstra’s patents include technologies for detecting, capturing, and processing asteroid materials, forming a toolkit for future mining missions. The fact that a small company is building such a patent portfolio underscores that startups see IP as a valuable asset, possibly for securing investment or licensing deals down the line.

China

It’s not only U.S. companies or allies taking part – the space mining IP race is global. In March 2025, a Chinese research team unveiled the country’s first homegrown space mining robot, a six-legged machine capable of anchoring itself to an asteroid’s surface for drilling and sample collection. The team has filed patents on the robot’s novel mobility and anchoring mechanisms to ensure it can operate in microgravity.

This example illustrates how universities and nations worldwide recognize the importance of protecting breakthroughs in space technology and how intellectual property rights are closely tied to national ambitions in space.

NASA & Other Government Agencies

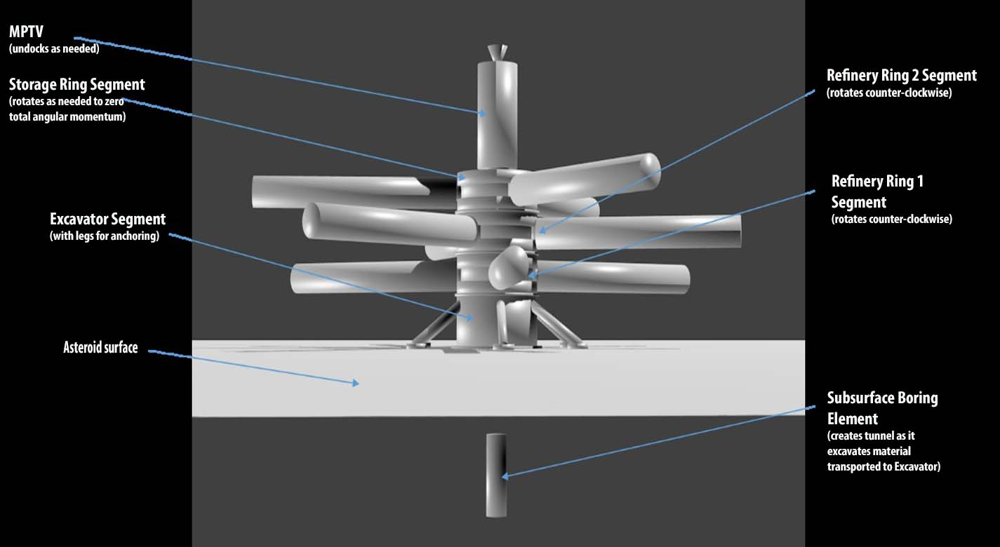

Government agencies are also in the mix. NASA itself has developed a concept for an orbital refinery spacecraft (depicted above) that can process asteroid material using artificial gravity. NASA has made this patent-pending technology available for licensing to private partners, indicating a collaborative approach where federal research can be transferred to U.S. companies.

Similarly, space agencies and research institutions in Japan, Europe, and elsewhere are pushing the technology envelope – and they, too, navigate IP law when spinning off innovations to the private sector. In some cases, agencies might choose not to patent but instead publish their findings (placing them in the public domain) to encourage wider use. In others, they secure patents but offer non-exclusive licenses to spur industry uptake.

How these patents are handled will influence who gains competitive advantages in the burgeoning space mining field.

Navigating IP Law in the Space Mining Era

Space mining sits at the intersection of radical innovation and legal frontier. As companies prepare to hunt for gold among the stars (or more likely, water ice and rare metals), they must also mind the legal bedrock beneath their feet – or lack thereof. The challenges of patenting space mining technologies under current laws include jurisdictional puzzles, enforcement uncertainties, and many unanswered questions about how old treaties apply to new tricks.

These legal grey areas, however, are starting to get attention as the industry matures. Clearer frameworks are gradually emerging through national laws like those in the U.S. and Luxembourg, and through international dialogues such as the Artemis Accords. For space enthusiasts and industry followers, this is more than just legal fine print. It’s about creating the conditions for a thriving space economy.

The Next Legal Chapter

Intellectual property law, dull as it may sound, is a key piece of the puzzle. Well-defined IP rights can encourage the massive investments needed to make space mining a reality by reassuring companies that their ingenious new drill, robot, or refinery won’t be free for all to copy. At the same time, the space community must balance exclusive rights with the ethos of cooperation and benefit for humanity.

That could mean new forms of licensing, patent pools, or international agreements to share critical technologies while rewarding innovators. In the coming years, expect to see more developments on this front. We may witness the first patent infringement claim arising from an incident in space, or the establishment of protocols between nations on honoring each other’s space-related IP.

The way these issues are resolved will help determine whether the space mining industry stays an open opportunity for many or a playground for a litigious few. One thing is certain: as we extend humanity’s reach beyond Earth, we’re also extending our legal and economic systems. Intellectual property law is part of the mission architecture for off-world ventures. By proactively addressing IP challenges, we can build a legal foundation that supports innovation, investment, and the shared dream of exploring and utilizing the final frontier – together.